http://www.seussville.com/

Seuss.

If you want to pronounce the name the way his family did, say Zoice,not Soose. Seuss is a Bavarian name, and was his mother’s maiden name: Henrietta Seuss’s parents emigrated from Bavaria (part of modern-day Germany) in the nineteenth century. Seuss was also his middle name.

Theodor Seuss Geisel — known as “Ted” to family and friends — liked to say that he adopted the name “Dr. Seuss” because he was saving his real name for the Great American Novel he would one day write. But that’s probably not true. When talking to the media, Geisel was more interested in telling a good story than he was in telling a true story.

The true story is also a good one, as we learn in Judith and Neil Morgan’s excellent biography Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel (the primary source for what you are now reading). During his senior year at Dartmouth College, Ted Geisel and nine of his friends were caught drinking gin in his room. This was the spring of 1925, and the dean put them all on probation for violating the laws of Prohibition. He also stripped Geisel of his editorship of Jack-O-Lantern — the college’s humor magazine — where Ted published his cartoons. To evade punishment, Ted Geisel began publishing cartoons under aliases: L. Pasteur, D.G. Rossetti ’25, T. Seuss, and Seuss. These cartoons mark the first time he signed his work “Seuss.”

As a magazine cartoonist, he began signing his work under the mock-scholarly title of “Dr. Theophrastus Seuss” in 1927. He shortened that to “Dr. Seuss” in 1928. In acquiring his professional pseudonym, he also gained a new pronunciation. Most Americans pronounce the name Soose, and not Zoice. And that’s how Ted Geisel became Dr. Seuss.

Dr.?

Dr. Seuss was not a doctor. Ted Geisel did consider pursuing a Ph.D. in English: After graduating from Dartmouth, he went to Oxford, where he studied literature from 1925 to 1926. I use the term “studied” loosely. Though his Oxford notebooks include some notes on the lectures, they reveal a much greater propensity for doodling.

One day after class, his classmate Helen Palmer looked over at his notebook.

“You’re crazy to be a professor. What you really want to do is draw,” she told him. “That’s a very fine flying cow!”

They got engaged, and she finished her M.A. Ted briefly contemplated becoming a scholar of the Irish satirist Jonathan Swift, but he realized that Helen was right. He really did want to draw. So, he left higher education, they returned to the U.S., and he became a cartoonist.

In 1955, Dartmouth gave him his first honorary doctorate. He would eventually receive several more honorary degrees, including one from Princeton. By pursuing his love of drawing, Ted Geisel became one of the few people to earn a Ph.D. by dropping out of graduate school.

Quick, Henry, the Flit!

Success was not immediate. Ted married Helen in 1927, and they moved into a walk-up apartment on New York’s Lower West Side while he tried to establish himself as a cartoonist. After a year of scraping by, Ted chanced upon the career that would make him famous: advertising. It all began when he happened to use a popular insecticide for a punchline. For a 1928 issue of Judge magazine, Seuss drew a cartoon in which a knight remarks, “Darn it all, another dragon. And just after I’d sprayed the whole castle with Flit!” The wife of an advertising executive saw the cartoon and asked her husband to hire Seuss to write ads for Flit.

In a typical Flit cartoon, large mosquitoes converge on a child at a picnic. His mother cries, “Quick, Henry, the Flit!” Father (Henry) looks for the Flit to save the day. In another, a ventriloquist’s dummy sees a giant insect heading for him. To the astonishment of the ventriloquist, the dummy shouts, “Quick, Henry, the Flit!”

Dr. Seuss’s ad campaign was a hit. “Quick, Henry, the Flit!” was the “Got Milk?” or the “Where’s the Beef?” of its day — a catchphrase that everyone knew. As Robert Cahn wrote in his 1957 profile of Seuss, “‘Quick Henry, the Flit’ became a standard line of repartee in radio jokes. A song was based on it. The phrase became a part of the American vernacular for use in emergencies. It was the first major advertising campaign to be based on humorous cartoons.”

Seuss went on to create ads for Holly Sugar, NBC, Ford, General Electric, and many others. For the next thirty years, advertising would remain Ted Geisel’s main source of income. The Cat in the Hat would change all that.

“You make ’em. I’ll amuse ’em”

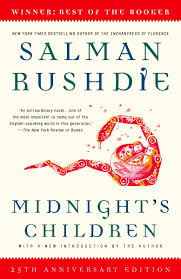

The Cat in the Hat (1957) was Seuss’s thirteenth children’s book. And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street (1937) was his first. He wrote an even earlier, unpublished children’s book in 1931.

Why did he decide to write for children? Geisel often said that a clause in his contract with Standard Oil (makers of Flit) prohibited him from undertaking many other types of writing, but not from writing children’s books. As he told scholar and Dartmouth librarian Edward Connery Lathem in 1975, “I would like to say I went into children’s book writing because of my great understanding of children. I went in because it wasn’t excluded by my Standard Oil contract.”

This might be true. However, given his tendency to embellish, there may be other truths he’s avoiding. Geisel wrote his first children’s book in the same year that Helen learned she could not have children.

To silence friends who bragged about their own children, Ted liked to boast of the achievements of their imaginary daughter, Chrysanthemum-Pearl. He even dedicated The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins (1938) — his second children’s book — to “Chrysanthemum-Pearl (aged 89 months, going on 90).” He included her on Christmas cards, along with Norval, Wally, Wickersham, Miggles, Boo-Boo, Thnud, and other purely fictional children. For a photograph used on one year’s Christmas card, Geisel even invited in half a dozen neighborhood kids to pose as his and Helen’s children. The card reads, “All of us over at Our House / Wish all of you over at / Your House / A very Merry Christmas,” and is signed “Helen and Ted Geisel and the kiddies.”

Perhaps curious to know what his own kiddies might have been like, in 1939 he and business partner Ralph Warren tried to invent an Infantograph, which promised to show how a couple’s children would look. Although they never quite got it to work, Geisel did write advertising copy for the camera’s expected debut at the World’s Fair: “IF YOU MARRIED THAT GAL YOU’RE WALKING WITH, WHAT WOULD YOUR CHILDREN LOOK LIKE? COME IN AND HAVE YOUR INFANTOGRAPH TAKEN!”

His fourth children’s book, Horton Hatches the Egg (1940), is about an adoptive father. Horton looks after Mayzie’s egg and, when it hatches, becomes the newborn elephant-bird’s parent.

People often asked Dr. Seuss how he, a childless person, could write so well for children. His standard response: “You make ’em. I’ll amuse ’em.” The question ignores the fact that many great children’s writers had no children of their own: Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear, Beatrix Potter, Margaret Wise Brown, Crockett Johnson, and Maurice Sendak, to name a few. That said, Seuss’s funny answer may conceal a private sadness. As he told his niece Peggy, “it was not that we didn’t want to have children. That wasn’t it.”

Or he may be telling the truth about the Standard Oil contract. Or both may be true.

When he married the former Audrey Stone, who in 1968 would become his second wife, Ted Geisel acquired two stepdaughters: fifteen-year-old Lark and eleven-year-old Lea. However, for over half of his career as a children’s author, Dr. Seuss had no children.

And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street

No one wanted to publish his first children’s book — an ABC of fanciful creatures, including the long-necked whizzleworp and the green-striped cholmondelet. Several years later, he tried once more with a new book. Again, publisher after publisher turned it down.

The new book had seemed like a good idea. Aboard a ship, crossing the Atlantic in 1936, Geisel kept himself entertained by putting words to the rhythms of the ship’s engines: “And to think that I saw it on Mulberry Street.” This phrase grew into a story of a young boy named Marco imagining an increasingly fantastic parade. When Geisel arrived back home, he revised the text, added illustrations, and created a picture book.

Depending on the version of the story he tells, either 20, 26, 27, 28, or 29 publishers rejected the book. Geisel was walking down Madison Avenue, about to throw the book away, when he ran into former classmate Mike McClintock, who had just been appointed juvenile editor of Vanguard Press. McClintock promptly took him up to his office (Vanguard’s offices were on Madison), where they signed a contract for Mulberry Street. As Geisel puts it, “That’s one of the reasons I believe in luck. If I’d been going down the other side of Madison Avenue, I would be in the dry cleaning business today!” Would Seuss really have gone into the dry cleaning business? That’s unlikely. But the “dry cleaning” line makes for a better story.

Know more about Dr. Seuss and might as well enjoy the cute site: http://www.seussville.com/

also see Facebook fanpage: https://www.facebook.com/Dr.Seuss